Imagine you’re a business owner trying to decide which product packaging will catch more eyes, or a government analyst choosing between two subsidy programs. What if you didn’t have to rely on guesswork or gut feelings? That’s where the magic of A/B Testing comes in—a scientific way to make smarter decisions by comparing two options directly. In the world of economic analysis, where every choice can ripple through financial systems and affect countless lives, A/B Testing is a game-changer.

It’s not just a tool for tech giants or marketers. From predicting voter turnout with different mail campaigns to determining which unemployment policy stimulates recovery faster, A/B Testing helps uncover what truly works. Think of it as the GPS for navigating complex economic landscapes—reliable, evidence-driven, and refreshingly clear.

Let’s take a deep dive into this fascinating approach and explore how it’s shaping the way we understand our economies.

What is A/B Testing?

A/B Testing, also known as split testing or bucket testing, is a method where two versions of a variable (A and B) are compared to see which one performs better. In the realm of economic analysis, this often means evaluating the outcomes of two different policies, programs, or strategies to determine which one yields more favorable economic results.

The idea is simple but powerful: isolate one factor, test two variations, measure the results, and let the data speak. It’s like having a controlled experiment in a real-world setting—a mini-laboratory for policy-makers, analysts, and investors.

Breaking Down A/B Testing

At its core, A/B Testing involves three main components:

- Control Group (A): This group experiences the current or baseline scenario.

- Treatment Group (B): This group is exposed to a new variation.

- Outcome Measurement: The effects on each group are measured and compared.

Example: Let’s say an economic research team wants to test two types of job training programs. Group A gets traditional in-person training, while Group B receives a digital course. After six months, they compare job placement rates. Whichever program yields higher employment rates wins.

This method is beloved for its clarity. There’s no room for “maybe” or “sort of.” Either Program B helps more people get hired, or it doesn’t. Period.

History of A/B Testing

Though A/B Testing feels modern, its roots stretch back nearly a century. The concept stems from the world of scientific experimentation and agriculture.

| Year | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 1920s | Ronald Fisher pioneers randomized control trials in agriculture. |

| 1950s | Medical researchers adopt similar testing for drug efficacy. |

| 1990s | Tech firms start using split tests for UX design. |

| 2010s | Governments and economists begin using A/B Testing for policy trials. |

In economics, it found its stride when randomized controlled trials (RCTs) started being used to assess microeconomic policies in developing countries. Nobel Laureates like Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee brought A/B Testing to the forefront of development economics.

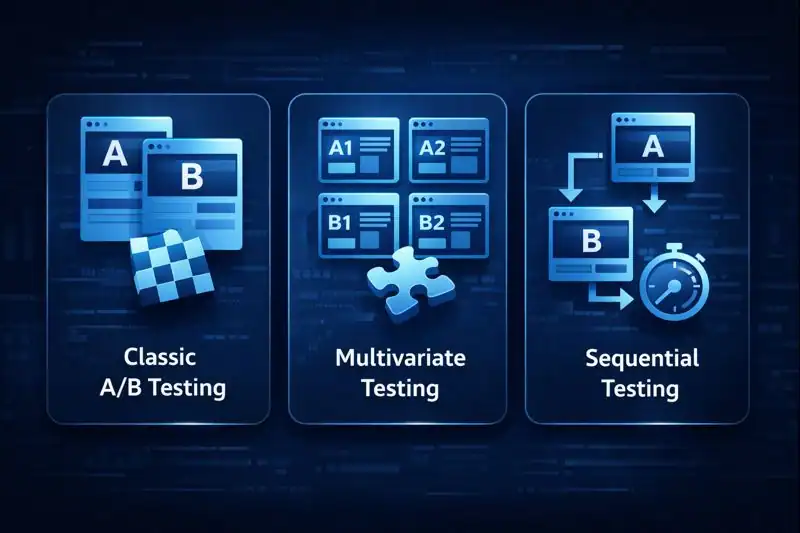

Types of A/B Testing

There’s more than one way to run a split test. Here are the most common types used in economic analysis:

A/A Testing

This test compares two identical groups to ensure the testing system is reliable. If results differ significantly, something’s wrong.

Example: Before rolling out a tax policy experiment, economists run an A/A test to confirm there’s no inherent bias in their randomization.

Classic A/B Testing

The standard model. Two different strategies go head-to-head.

Example: Comparing two different subsidies to see which boosts small business growth more effectively.

Multivariate Testing

Tests several variables simultaneously to see how they interact.

Example: Evaluating how changes in minimum wage + tax credits together impact low-income household spending.

Sequential Testing

Allows ongoing evaluation so the test can be stopped early if one option is clearly better.

Example: During a market crash, testing immediate vs delayed stimulus response strategies.

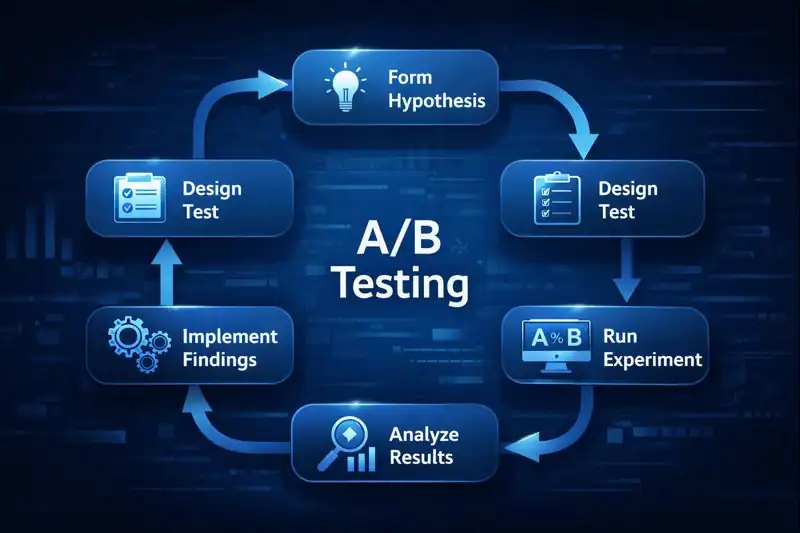

How Does A/B Testing Work?

Here’s how a typical A/B Testing setup unfolds in economic analysis:

- Identify the Problem or Hypothesis

Suppose analysts want to reduce unemployment. The hypothesis: Training Program B is more effective than Program A. - Design the Test

Randomly assign participants to each group. Ensure everything else is consistent—only the program differs. - Execute the Test

Run both programs for a set period (say, 6 months). Monitor variables like job placement, income increase, and satisfaction. - Analyze Results

Use statistical analysis to determine if the outcome differences are significant—not just lucky guesses. - Implement the Best Option

If Program B significantly outperforms A, roll it out on a larger scale.

This structured approach minimizes biases, reveals hidden truths, and empowers data-backed decisions.

Pros & Cons

Before jumping in, it’s worth weighing the strengths and limitations of A/B Testing.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Clear, data-driven decisions | Can be time-consuming |

| Reduces guesswork and bias | Requires careful planning |

| Real-world applicability | Limited to testing two main options at once |

| Scalable across sectors | Ethical concerns in sensitive areas |

Despite its challenges, the clarity it provides often outweighs the drawbacks.

Uses of A/B Testing

A/B Testing is everywhere in economic analysis, from micro to macro levels. Whether you’re an academic, investor, or policy-maker, there’s a use case with your name on it.

Government Policy

Cities and governments are increasingly using A/B Testing to fine-tune large-scale economic initiatives. For example, a city might trial two versions of a universal basic income (UBI) program—one providing unconditional monthly payments, and another linking payouts to work or community service. The results, measured in terms of citizen well-being, employment rates, and spending behavior, can significantly influence broader national policy decisions.

Social Programs

In the realm of social support, A/B Testing helps policymakers determine which models best serve communities. Consider a test comparing two affordable housing grant programs: one allocates funds based on household income, while the other prioritizes residents in high-rent locations. By analyzing the outcomes—such as housing stability and quality of life—decision-makers can deploy more effective and equitable assistance strategies.

Economic Research

Economists frequently use A/B Testing to uncover what influences financial behavior. One such example involves testing whether different types of tax reminders affect compliance rates. Half of the recipients might receive email prompts, while the other half gets physical letters. By comparing the resulting payment behaviors, researchers can advise tax authorities on the most cost-effective and impactful communication strategies.

Business Economics

Businesses also lean on A/B Testing to guide strategy and investment. A retailer, for instance, might experiment with two promotional campaigns—one offering a percentage discount and another bundling free products. Tracking customer response and sales performance helps identify which promotion drives higher revenue and engagement, feeding valuable insights into their broader investment plan.

Crisis Response

During turbulent times such as a market crash, A/B Testing can help economists and governments respond swiftly and smartly. Imagine testing two economic rescue strategies: direct cash transfers to households versus funding for infrastructure projects. By assessing which approach more effectively boosts consumer confidence and spending, decision-makers can act based on real-time evidence rather than speculation

Resources

- Harvard Business Review – A Refresher on A/B Testing

- NBER – Using Randomized Controlled Trials in Development Economics

- World Bank – The Impact of A/B Testing on Public Policy

- Google Optimize – Guide to A/B Testing

- J-PAL – Evidence from Field Experiments