Let’s be real for a second—cybersecurity can feel like a never-ending game of digital hide-and-seek. You patch one vulnerability, and a new one pops up the next day. But among the many sneaky threats out there, it stands out as one of the most insidious. It’s the ghost in the machine, quietly working behind the scenes, invisible to most detection tools and often even to seasoned IT pros.

I remember the first time I heard about it. I was fresh into cybersecurity, bright-eyed, and convinced I could outsmart any cyber threat with a few clever lines of code and a strong firewall. Then came a story about a corporate breach that had gone undetected for six months. The cause? A rootkit buried so deep it was practically in the digital underworld. That story stuck with me—and it’s why understanding rootkit is crucial in today’s cybersecurity landscape.

What is Rootkit?

The malware is like a digital shapeshifter—it hides in plain sight, manipulating your operating system to conceal its presence. The term comes from “root,” the superuser account in Unix/Linux systems, and “kit,” which refers to the set of tools that enable unauthorized access to a system.

Think of a suspicious software as a stealthy parasite. Once it’s inside your system, it hooks into critical functions, hides files, intercepts data, and can even remotely control your computer—without you having the faintest idea it’s there. It’s the Houdini of malicious software, making itself invisible to traditional antivirus programs.

Breaking Down Rootkit

So what’s under the hood of a rootkit?

A typical malware isn’t just one tool—it’s a whole suite of them, designed to blend into your system’s processes like a digital chameleon. Here are its core components:

- Loader: The mechanism that injects the malware into the system, often via a trojan or phishing scam.

- Hider: Masks the rootkit’s presence by manipulating system files, registry entries, and running processes.

- Backdoor: A hidden gateway that allows remote attackers to access the system at will.

- Command and Control (C2): Where the attacker sends instructions to the infected machine.

Example: In 2005, Sony BMG notoriously used a the suspicious software in their music CDs to prevent copying. Ironically, this opened up users’ systems to real cyber threats—because the rootkit’s cloaking features could be exploited by hackers. Lesson? Even well-intentioned uses can go sideways fast.

History of Rootkit

The origin of the it dates back to the early 1990s. Initially, it was more of a hacker’s pet project than a widespread threat.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1990 | First known spyware developed for SunOS by Lane Davis and Steven Dake. |

| 1999 | First Windows rootkit discovered—NT Rootkit by Greg Hoglund. |

| 2005 | Sony BMG scandal sparks public awareness. |

| 2008 | Mebroot infects Master Boot Record (MBR), becoming nearly undetectable. |

| 2010s | It evolves to infect firmware and hypervisors, dodging even low-level scans. |

It’s evolved from a novelty into a full-blown cybersecurity nightmare, especially as modern rootkit variants can embed themselves into firmware—making them almost impossible to remove without specialized tools or hardware replacements.

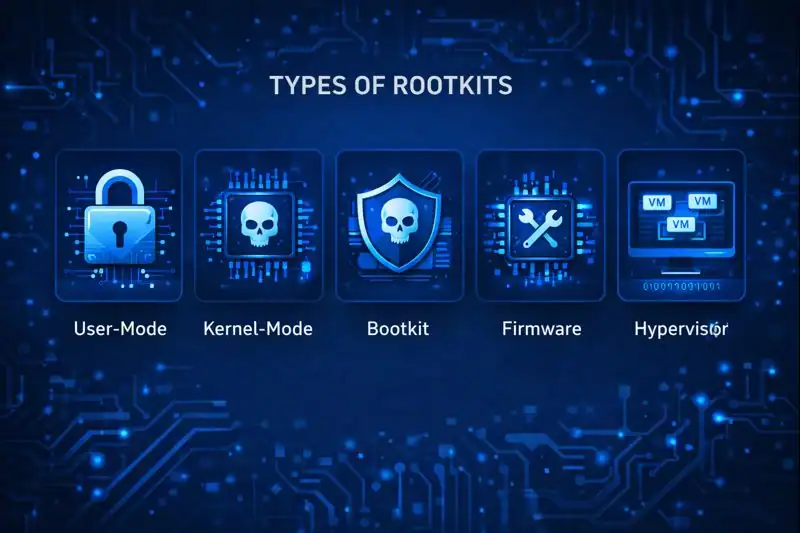

Types of Rootkit

There’s no “one-size-fits-all” when it comes to rootkit. Let’s dive into the types you should know:

User-Mode

These operate at the application level. They intercept calls to standard APIs and manipulate data before it’s displayed to the user.

Example: HackerDefender was a user-mode rootkit that could hide files, processes, and registry entries from Windows.

Kernel-Mode

These live in the system’s core—its kernel. They’re harder to detect and more dangerous because they operate with the highest level of privilege.

Example: The infamous TDL-4 modified Windows kernel code to hide its processes and files.

Bootkit

This type infects the Master Boot Record (MBR) or UEFI firmware. It’s loaded even before the OS starts.

Example: The Mebroot rootkit that rewrote MBR code.

Firmware

They infect firmware, like BIOS or network cards. They can persist even after reinstallation of the OS.

Example: LoJax was the first rootkit discovered in UEFI firmware, targeting espionage victims.

Hypervisor

Also known as Virtual Machine Based Rootkits (VMBRs), they install themselves below the OS using a hypervisor, creating a virtual environment to run the actual OS.

Example: SubVirt by Microsoft and University of Michigan researchers was a proof-of-concept VMBR.

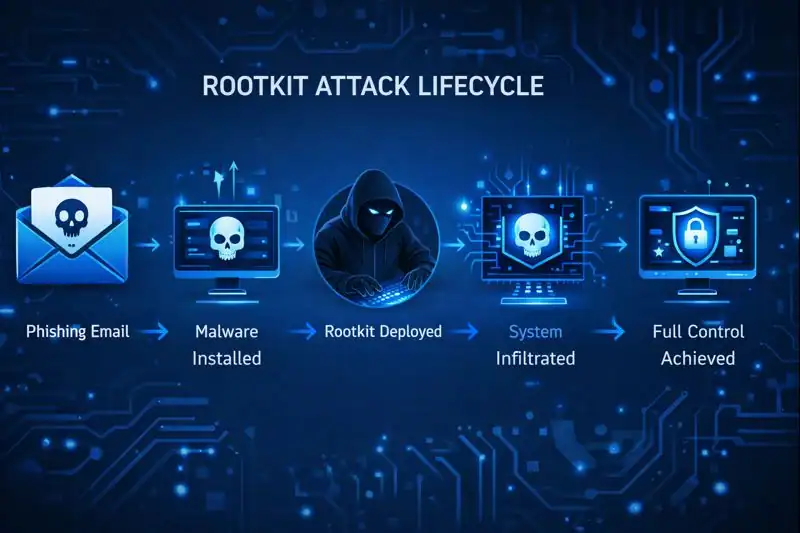

How Does Rootkit Work?

Let’s walk through how a rootkit silently invades your system:

- Delivery: A phishing email arrives, disguised as a harmless PDF. You click it. Boom—malware enters.

- Installation: The malware drops a worm payload onto your system, often via privilege escalation.

- Cloaking: The worm hides its tracks by altering system processes, making itself invisible to Task Manager and antivirus.

- Control: A backdoor opens. The attacker now has unrestricted access to your system, data, and even your webcam (yes, it happens).

- Persistence: Even if you reboot, reinstall, or update (like that recent Windows Update you trusted), the suspicious malware might still be there, lurking in your firmware or boot sector.

Pros & Cons

While the term rootkit is almost universally tied to malicious use, it has had rare applications in ethical hacking and software testing.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Can be used in ethical hacking to test system robustness | Difficult to detect and remove |

| Useful for stealth monitoring in rare authorized use cases | Grants complete control to attackers |

| Can aid in reverse engineering or deep system access | May survive OS reinstalls and updates |

| Encourages development of stronger detection tools | Highly dangerous if used maliciously |

Uses of Rootkit

While malicious use dominates the conversation, it has shown up in various contexts.

Cyber Espionage

Nation-states use it to spy on rival governments, stealing intelligence while staying under the radar. This was seen in operations like Turla, which embedded rootkits to track diplomats.

Corporate Surveillance

Some corporations have controversially used it to monitor employees or enforce digital rights—though it’s often criticized and legally risky.

Malware Obfuscation

Cybercriminals integrate its functionality to keep their payloads undetected by security systems—perfect for long-term infiltration and data theft.

Ethical Hacking & Penetration Testing

Ethical hackers may simulate suspicious software’s behavior (legally!) to test how well a company can detect stealth threats, though they never use it on live environments without consent.

Security Research

Academics and researchers build malware models to explore vulnerabilities and build better defenses. Think of it as fighting fire with controlled fire.

Resources

- CSO Online – What is a Rootkit?

- Kaspersky – Rootkit Explained

- Symantec – Rootkit Detection and Removal

- MITRE – ATT&CK Framework

- TechTarget – How Rootkits Work